Opinions and Expertise

Is the data-driven age of marketing attribution coming to an end?

Why “dark social” habits, tighter privacy laws, and impending tracking limitations are forcing marketers to rethink attribution in a cookieless future.

Data and attribution have long governed digital marketing. Most marketers (like myself) rely on third-party tracking to understand what channels and tactics are performing – assuming it’s “trackable” to begin with – and where to spend the budget. Now, factors beyond our control are putting traditional attribution models under threat. But is that such a bad thing? Some think it’s a blessing in disguise.

In recent years, tighter privacy laws such as GDPR and CCPA empowered audiences to take control of their data by opting out of cookies (small text files that websites save to your browser containing data about you and your online browsing activity).

To add insult to apparent injury, Apple rolled out App Tracking Transparency (ATT), requiring developers to ask users for permission to track their activity in third-party apps and websites. This was the latest in a series of moves from Apple to limit tracking, with further changes expected with the next iOS update. Google to roll out similar policies in 2023.

In short: tracking online behavior is getting increasingly complex, and the tools we use to target, personalize, and optimize campaigns are becoming less and less effective. Attribution is on the brink of extinction.

But the problem is bigger than people opting out of cookies. Marketers are starting to realize that human behavior isn’t quite as trackable as they once thought – go figure! For example, what Google Analytics registers as direct traffic is often skewed by something called “dark social.”

Sounds bad, right? Well, it’s not. Dark social is simply a term to characterize what happens when people share content (links, screenshots, images, even word-of-mouth recommendations) on social channels and messaging platforms without trackable referral codes like UTMs. But for marketers reliant on attribution (which is most of us), the lack of visibility that ensues is a game-changer.

Direct(ing) traffic in the dark

When I find something interesting online, be it on a website or social media platform, I want to share it with people. That’s just modern human behavior – we are chronic oversharers. When it comes to a piece of content online, do I click the trackable ‘share’ button? Maybe. But I’m more likely to copy and paste the URL into an email, text message, or Slack channel. I might even screenshot it and forward it along to friends and colleagues.

And I’m not alone. Researchers at London South Bank University found that 17% to 18% of website traffic comes from invisible social sharing. Dubbed “dark social” by journalist Alexis Madrigal in a 2012 article for The Atlantic, this behavior introduces a big hurdle for attribution-focused marketers: Google Analytics can’t distinguish it from other direct traffic sources.

When up to 53% of visitors come from direct traffic (according to Alexa Internet, Amazon’s soon-to-be-retired web traffic analytics company), that’s a large chunk of traffic to be in the dark about, pun intended.

As dark social demonstrates, how humans behave when finding and buying products is complex, and it begs the question: are attribution models giving marketers a clear view in the first place? Attributing success to one channel is innately flawed because it fails to acknowledge the work that other channels contribute.

The buying journey is a complex funnel; the first, second, and sometimes even third time customers hear about your brand all work together to impact a prospect. There have always been tactics that influence purchase decisions that we can’t track, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do them. Their impact is real – even if traditional attribution models say otherwise.

A more holistic approach

When marketers can’t rely on tracking, research and instinct become much more critical. But it doesn’t mean investing in channels without a measurement plan; there is still value in analyzing the data.

Keeping an eye on upper funnel metrics, such as impressions, engagement, and clicks, is essential. While many may call these “vanity metrics,” they' re still a strong indicator of what' s working and what’s not.

But metrics alone aren’t enough. Marketers need to find ways to speak with (and hear from) their audience. Attribution surveys, for example, enable marketers to collect actionable zero-party data without users feeling like their privacy is at risk.

Our take

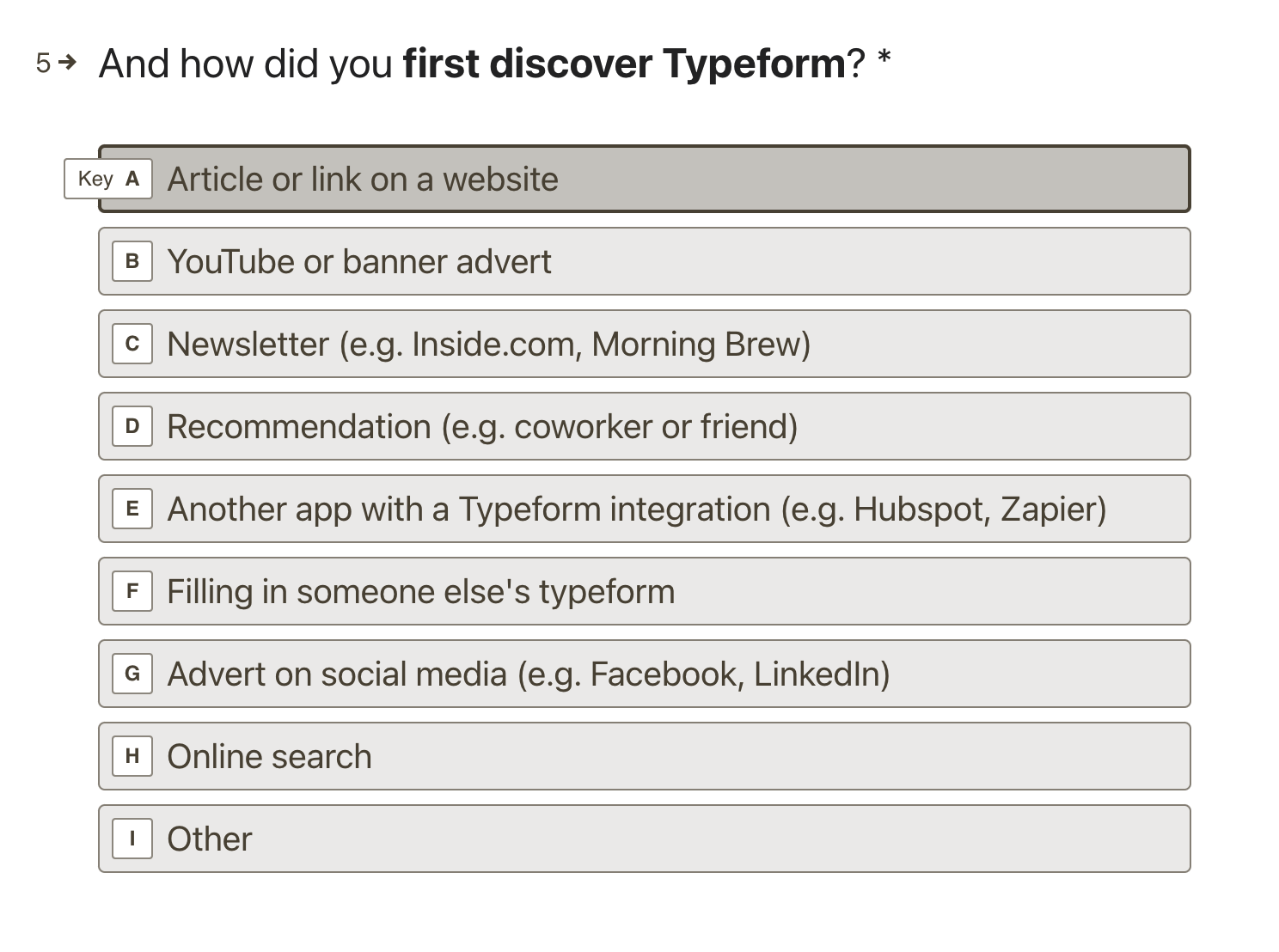

At Typeform, we use a simple attribution survey sent to new users (free or paid) to ask, “how did you first discover Typeform?” accompanied by a dropdown list of various marketing tactics.

It has been helpful to verify what we’re seeing on other platforms (i.e., Google Analytics and our internal attribution model), but it’s not perfect. Why? Because a definitive list will never cover every possible option. If it did, it would be overwhelmingly long and impossible to maintain because, like most marketers, we’re constantly testing new tactics and channels.

With that said, we are exploring the idea of A/B testing and using conditional logic to ask a portion of these respondents the same question but with an open-ended response. We’re hoping to see more anecdotal feedback like, “a colleague sent me an article from Typeform on LinkedIn,” which would tell us our content is resonating and being shared on LinkedIn, shedding light on this dark social activity. In this scenario – with our current dropdown list – the respondent might select “Recommendation” or “Advert on social media,” leaving too much room for interpretation.

The takeaway

The supposed precision of marketing attribution was too good to be true. Cookies made us think we had GPS trackers on all our prospects and customers, watching their every move and understanding their “behavior” based on what they were doing online. In reality, that was never the case. And with tightening privacy laws and increasingly strict tracking limitations, it will be all the less so.

So, it’s back to basics. And back to genuinely trying to understand our target audience by speaking with them and hearing from them. We no longer have the luxury of ignoring “anecdotal” feedback and instead should learn to rely on it. That’s the point of zero-party and first-party data, right? It' s direct from the source.

.png)

.png)