The steady rise of makers

I just arrived home from Barcelona and was catching up with a friend (we’ll call him Lee). As we’re talking, I notice a roll of batteries wrapped in black electrical tape sitting upright on a chessboard.

“What’s that?,” I ask.

“Those are batteries I pulled from a few laptops. I’m gonna make a ‘Tesla’ battery out of them,” he replied, referencing the new Powerwall from Tesla that provides energy for residential homes. “It’s going to power my AC this summer.”

Latest posts on Tips

“Oh.”

He slid a schematic of his prototype toward me and continued: “I’m also going to create a windmill out of a fan. It should generate enough juice to keep the battery charged. If all goes well, my energy bill should be less than $25.”

At this point I’m thinking, “WTF got into you?”

Only later on do I realize, it’s not just him.

From 1964 to 2014, the number of applications for patents in the United States shot through the roof. The number of patents granted is usually about half of the total submitted in a given year. But the point is: more and more people are making stuff.

Pretty cool. But how many of those patents became successful, profitable businesses? How many inventors, tinkerers, and builders are sustaining themselves with their products? It’s one thing to research and develop something, but it’s quite another to build a successful business around it.

Why businesses fail

Here’s what I mean. In 2014, Fortune magazine published an article titled Why startups fail, according to their founders. In it, they cited postmortems done on 101 startups (a postmortem explains why a company ‘died’, according to the CEO or other insider). Here’s the main reason why startups fail, as cited by 42% of polled startups:

“…the number-one reason for failure, is the lack of a market need for their product.”

Business lesson #1: If no one wants your product, you don’t have a business—period. But how many startups build things people don’t want with the irrational hope that they’ll convince them otherwise?

Can you imagine? Going through all the trouble of building something (because you think you have a great business idea) and nobody wants it? You spent an inordinate amount of time and money thinking, designing, and developing something only to discover that your efforts were in vain. How demoralizing.

The good news is this situation is totally preventable. How? If 100% of makers simply validated their ideas first, I’m sure they could knock that number down significantly.

This guide will show you how to validate your next big idea—and prevent unnecessary costs and heartache. After all, if this idea doesn’t work out, you can always move on to the next one quickly and easily without losing your shirt, and more importantly, your confidence.

C’mon. Let’s get started.

Business validation overview

Validating a new business idea doesn’t have to be complicated. There are three essential stages in the validation process.

Stage I: Market validation

Stage II: Idea validation

Stage III: MVP (minimum viable product) validation

Ideally, you’ll want to validate your market first, before testing your solution. Then put the necessary resources into building your MVP. But business validation is not a linear path. Some people jump right into the idea or solution because they’re scratching their own itch. Think Sara Blakely (Spanx), Stepan Pachikov (Evernote), or even J.K. Rowling (Harry Potter).

You don’t have to start at “market validation” to be effective, but you’ll want to revisit it later to refine your product/market fit. If you’re starting from scratch, it makes more sense to start there.

Let’s talk about each validation stage in more detail.

Stage I: Market validation

When Gary Halbert, the legendary copywriter, taught workshops, sometimes he would begin his classes with the following scenario:

“If you and I both owned a hamburger stand and we were in a contest to see who could sell the most hamburgers, what advantages would you most like to have on your side to help you win?”

According to Halbert:

“Some of the students say they would like to have the advantage of having superior meat from which to make their burgers. Others say they want sesame seed buns. Others mention location. Someone usually wants to be able to offer the lowest prices.

So I tell them, ‘O.K., I’ll give you every single advantage you have asked for. I, myself, only want one advantage and, if you will give it to me, I will (when it comes to selling burgers) whip the pants off all of you!’”

“What’s that?” they ask.

“The only advantage I want is a starving crowd!”

This is a short lesson in market validation. Your goal at this stage is to find a starving crowd—or a market. Gary Bencivenga, who some consider the greatest copywriter of all time (maybe the name “Gary” is predestined to sell stuff), once said:

“Problems are markets.”

Obviously, if people are hungry, that’s a problem. If people are feeling disconnected from each other, that’s a problem. If someone’s bored, that’s a problem.

Think about any market. You’ll find a ton of problems. The more urgent the problem, the more likely someone is willing to spend money. Think health, business, or education. Or the reverse of those—illness, lack of business, or ignorance.

Your starving crowd is all around you. But how do you know which market is the right one to go into? Well, that depends on a number of factors. You know your skills. You know what you’re interested in. Those are great places to start, but here’s what I usually suggest to people with no idea where to begin: find a problem you’re passionate about solving.

That’s right. Don’t find your passion first, because you may not be able to monetize it. Instead, find a problem that you’re passionate about. Then toss that problem into a blender with your unique knowledge, skills, and interests.

Once you figured that out, find a market that’s willing to pay. Here are three ways:

keyword research

Amazon search

run a “deep-dive survey”

Understand market size with keyword research

Open a Google Adwords account so you can access their Keyword Planner tool. This tool will allow you to see what people are searching for online, giving you an idea of potential markets.

People have no shame typing in their deepest, darkest secrets into that tiny search box. Google keeps track of every search, tells you how often people are looking for a certain keyword phrase, and boom! You have all the market data you need. Number of searches, how much competition there is for a certain keyword, and how much people are paying (on average) to advertise using that keyword phrase.

Next, go to keywordtool.io to do one more search. Now you’re going to scrape search results for questions that your market is asking. It’s pretty straightforward. Type in your search term, like “content marketing.” After you hit enter you’ll get a list of keywords. Directly under the search box, you’ll see the “questions” tab. Click on that, and you’ll get a list of questions that people are asking. There’s a nifty “copy” button so you can grab all those questions and place them in your favorite spreadsheet.

You’re off to a great start.

Using Amazon as a market research tool

Amazon acts as a great search engine for market validation. Find popular products and see how you can improve or augment them by looking at 1—3 star reviews. For most products, if it’s not on Amazon, then there’s probably not a starving crowd (unless it’s an app or software solution).

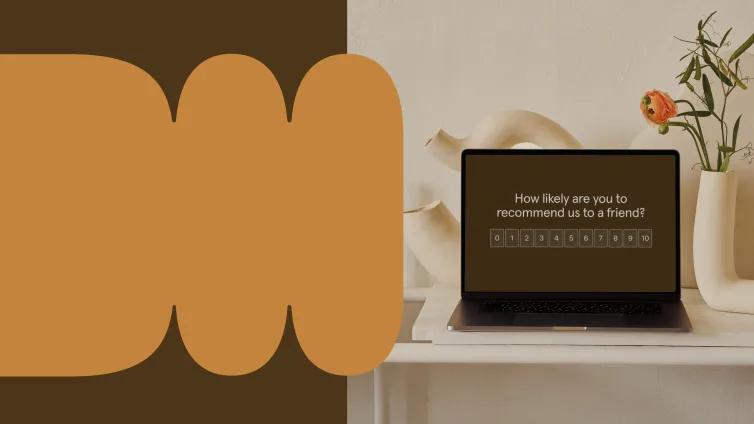

The deep-dive survey

What if you knew ahead of time which market to enter, what products to sell to that market, and the natural language that market uses to talk about their pain points? Would that be an advantage for you?

The “deep-dive survey” comes from Ryan Levesque, author of Ask., an excellent tool for understanding any market you’re looking to enter.

It begins with the premise/assumption that neither you nor your potential customer knows what they want. Ryan makes a strong case that most market research surveys focus on the wrong questions, and he’s narrowed it down to one revealing, but critical question:

What’s your single biggest challenge/frustration with____?

If you’re thinking about selling fountain pens, then your question would be:

What’s your single biggest frustration with fountain pens?

If you’re thinking about building a photo editing app, again:

What’s your single biggest challenge with photo editing apps?

Simple, right? But how does this question work for you?

First, it allows someone to answer accurately about something they don’t want. If you asked them what they wanted instead, they would be forced to make up a solution on the spot, and chances are they wouldn’t be able to do it because they would’ve solved their problem already if they could.

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

Second, this question tells you about your respondent’s recent experience with a particular challenge. If you sent this question to active users in this market, these frustrations and challenges would still be fresh in their minds.

Finally, asking this particular open-ended question allows people to answer any way they like. You want to encourage respondents to provide as much detail as possible.

When done with the right audience, the deep-dive survey gives you the precise pain points, the exact language your market uses (this is useful for writing copy and sales scripts), and enough details about your target market to determine if you should take the plunge or not. It also minimizes survey fatigue and reduces the number of questions asked.

So start with the “challenge/frustration” question first. Then follow that question up with this simple A/B multiple choice question to segment your audience into different buckets. Why? Because you’re likely to uncover niche markets where you can offer more custom solutions.

Using our photo editing app as an example, the follow-up question would look something like this:

Which of the following best describes you?

I use photo editing apps at least 3—4 times a week.

I use them 3—4 times a month.

For all the people who answer #1, ask a follow-up question, using the same language to further segment your audience. Like this:

Which of the following best describes you?

I am a graphic designer.

I am a studio photographer.

I am a wedding photographer.

I am nature photographer.

I am a photojournalist.

See how this whole process helps you identify your market more accurately? It’s a great way to validate your next market (=starving crowd) and segment your audience. I highly recommend Ryan’s book to learn the nuances of using surveys to make, market, and refine your next product or service.

Let’s move on to validating your solution.

Stage II: Idea validation

Okay, so you validated your market, but you don’t have a product or a service to offer. You haven’t designed or built anything yet. What can you do?

Let’s list them out:

Website + ads

Alex Brola, co-founder and president of CheckMaid.com, which runs an online, on-demand cleaning service told Entrepreneur Magazine:

“We actually validated [the idea] without having any cleaners to do the cleanings. We threw up a site, a booking form, a phone number, and ran some [pay-per-click] ads through Google and Bing, and saw what the conversion rate would be had we actually had cleaners.”

You take an idea, build a simple website offering your services, and drive traffic through ads.

In-person validation

Sometimes you solve a problem that potentially affects everyone. When that’s the case, you can start having conversations with just about anyone. In his book, Will It Fly?, Pat Flynn talks about his coffee shop validation.

As Pat waits in line for coffee, he turns around and offers to buy the person behind him a cup of coffee. Once someone accepts, he asks them for a moment of their time to answer a couple of questions (reciprocity in action). Pat explains that he’s an entrepreneur and looking to validate a business idea. People are usually responsive and Pat gets validation for the price of a cup of coffee.

Another example comes from Aaron Patzer, founder of Mint.com. Mint is a personal finance web app that connects to your bank, categorizes transactions, then uses an algorithm to determine where you can save money. For example, if the amount of money in your savings account could yield a higher interest rate somewhere else, Mint would pass that information on to you. Same with credit cards, your cable bill, or any recurring expense. Mint makes money whenever someone takes its advice as an affiliate for all recommendations.

Explaining the process he adopted for validating Mint, Aaron says:

“When I started Mint I took a very different approach… and this is sort of the methodology that I formed (Validate your idea > Create a prototype > Build the right team > Raise funding).

And did he do it the conventional way? Nope:

“Number one is to validate your idea. I actually didn’t write a line of code until I did about three or four months’ worth of thinking on Mint, which I think is counter to what a lot of people will suggest. A lot of people will say ‘Just get the product out there, just iterate very, very quickly, (and) just make a prototype.’”

Aaron approached different venture capitalists with his idea, but they told him the same thing. No one will trust you with their financial and personal information.

So what did Aaron do? He went to the local train station with three different product concepts written on a piece of paper. He asked random people what they thought of his solution as they waited for their train (they didn’t have anything else to do but wait around, according to him).

Then Aaron hit on a concept that sealed the deal. When asking people if Mint sounded secure to them, more of them said “yes” after he added the following phrase: bank-level data security.

Once “maybe” and “no” turned to “yes,” Aaron simply had to build it. Mint went live in 2007. In 2009, he sold Mint to Intuit for $170 million dollars.

Those two examples should give you some ideas on how to test your idea first. Write a few headlines or offers, get in front of your target market, and ask them for a few moments of their time.

But perhaps you have the itch to build or design something first. That leads us to the final stage.

Stage III: Minimum viable product (MVP) validation

What does MVP mean?

Normally, when someone says, “validate your MVP,” they’re talking about your “minimum viable product.” But validating your service works here too.

Minimum viable product doesn’t mean a half-baked cake. An MVP must work, first and foremost, then it must either prove or disprove your business idea. It has to be desirable and complete (whether it’s version .05 or 1.0) or your product is not ready for the public. Also, when you think minimum, think “cake.” Brandon Schauer from Adaptive Path came up with the “cake” model for product strategy.

For example, your initial idea is to bake a huge wedding cake with all the trimmings. Great cake, frosting, decorations, candles, sprinkles, whatever your ultimate user wants. Do you start making the best cake ever and try to sell that? No. You start small. You don’t want to invest a ton of time and resources into building a product nobody wants, right?

So start with a cupcake. Get yourself sorted with a project plan and some tools then start to build, test and learn. The point is that the first version must be useful and remarkable without losing your shirt in the process.

This concept from Spotify accurately explains the MVP process.

In the top half of this visual, you’ll notice that there’s not a usable version of the product until stage 4. In the bottom half, you have a usable product from the get-go. By the way, if you haven’t read How Spotify Builds Products, it’s an invaluable resource.

So don’t go too far in building your best idea. It’s likely that you can do just enough to get it validated without intense designing, coding, and paying a ton in ads. If you’re building an app, sketch it on paper first, and describe it to your user in person.

If you’re faster with digital tools, use Keynote or PowerPoint to make your MVP. Google Ventures are well known for using Keynote to build quick prototypes.

In fact, Google Ventures just released Sprint, a great guide to building prototypes in 5 days. I highly recommend it.

Validating services

SeekPanda sought to validate their language interpretation services. They used Typeform as their main landing page before investing in website design (smart way to save money). They drove traffic through ads and the rest is history. As Matt Conger explained it to me:

“Traveling for business is stressful enough. Especially in a country like China, where SeekPanda was started. We wanted to bring real-time booking to the interpreter industry. Our goal was for users to need less than one minute to fill out a form, and less than one minute to receive a personalized response.

Users would only see 6-12 questions from our bank of 30+. We hacked improvements to Typeform’s calculator feature to present personalized prices based on user answers.

Our conversion rate on our homepage increased by a factor of 4x.”

Here’s how their MVP looked using Typeform:

Once Matt and co. validated their idea, they dropped some cash on a better website design.

Running Ads

Use Google Adwords, Facebook ads, or focus on LinkedIn to offer B2B services.

Before writing your ad, make sure you spend plenty of time working on your headline. Even the best products in the world are obsolete if you can’t get your market’s attention. A headline is the ad for your ad. You’ll need a good one.

Here’s a handy guide to give you some tips when writing your next headline.

Product validation

The best way to validate any product is by demonstration. If you can demo it in person, so much the better, but a video demo works too. Think Youtube, Vimeo, or some other video hosting platform.

The most famous use of infomercials came from two well-known pitchmen, Ron Popeil and Billy Mays. Watch them if you want a master lesson in validating physical products.

Can you imagine a t-shirt business that earned over 2 million dollars in 30 days? Charlie Jabaley, manager of Rapper 2 Chainz told Shopify: “We just didn’t have a good track record selling merchandise like t-shirts.” After selling eight total t-shirts the first day they were available, Jabaley notes: “It was absolutely terrible.”

How do you go from selling 8 t-shirts to 2 million dollars? Here’s the formula:

Starts with a t-shirt design

Post designs on Instagram

Analyze and use follower behavior and feedback to iterate

Kill unpopular designs

Turn popular designs into merchandise that generates millions of dollars

“Now we understand exactly what people want,” Jabaley says. “We know in real-time what’s popular and what’s not, which really de-risks the merchandising process and allows us to make only what fans are willing to buy.”

Around Christmas, Jabaley posted a “dabbing” Santa sweater. Without inventory, he posted it on their ecommerce store and the result was their first big hit.

The sweaters generated $20,000 that day.

They did $30,000 the following day.

The sweaters went on to do $2.1 million in 30 days.

The tools for validation? Instagram and a good designer.

Digital products

Many SaaS companies in the B2B space allow free trials or demos of their products. You could apply the same tactic and offer your digital product for free to a select few “beta” testers in exchange for testimonials.

Free samples still work. Amazon allows browsers to read the table of contents and first chapter of a book to lure them into buyers. If you’re offering a book or a course, then share one of your best lessons for free. Add value before you take their money.

Ultimately your goal is to get your product in front of others as fast as possible. Collect feedback, then iterate and improve. Get it out there again. Repeat the process until you have something that’s useful and people are happy to pay for.

Getting traction

There’s one more thing to consider as you develop your MVP into a sustainable, repeatable business. Is your product matched with the right market? Remember the starving crowd analogy? If you make foot-long calzones and your market is starving for foot-long calzones, then you’re obviously a great match. This is called product/market fit.

The question is, will your market buy from you again? Why or why not? Could another competitor easily fill their needs? Can your customer live without you? What can you do to improve the product so it’s better for customers? Ask your customers these questions as you fine-tune and tweak your product or service to approach that elusive holy grail of product/market fit.

Final thoughts…

Validation is a great feeling. But imagine the opposite scenario. When you don’t feel validated. When you don’t have any proof that you’re on the right track. Your confidence turns to skepticism.

Confidence is another word for trust. If you don’t trust yourself, you won’t have the conviction you need to push a project forward. And nothing kills the creative spirit faster than doubt.

And how do you develop trust/confidence? Through practice. It’s the only way. When you push more and more ideas out to the public, when you shoot for volume and speed, you’ll naturally get better. Like anything, if you haven’t done it before, it may seem awkward at first. You’ll feel incompetent. That’s normal.

Practice is the fastest way to learn and learning is your competitive advantage.

But even with all that practice, if you don’t get validation from the outside, you don’t have a business. Good luck.